On Saturday NASA's Juno spacecraft, which has been orbiting Jupiter for the better part of a decade, made its closest flyby of the innermost moon in the Jovian system.

The spacecraft came to within 930 miles (1,500 km) of the surface of Io, a dense moon that is the fourth largest in the Solar System. Unlike a lot of moons around Jupiter and Saturn, which have surface ice or subsurface water, Io is a very dry world. It is also extremely geologically active. Io has more than 400 active volcanoes and is therefore an object of great interest to astronomers and planetary scientists.

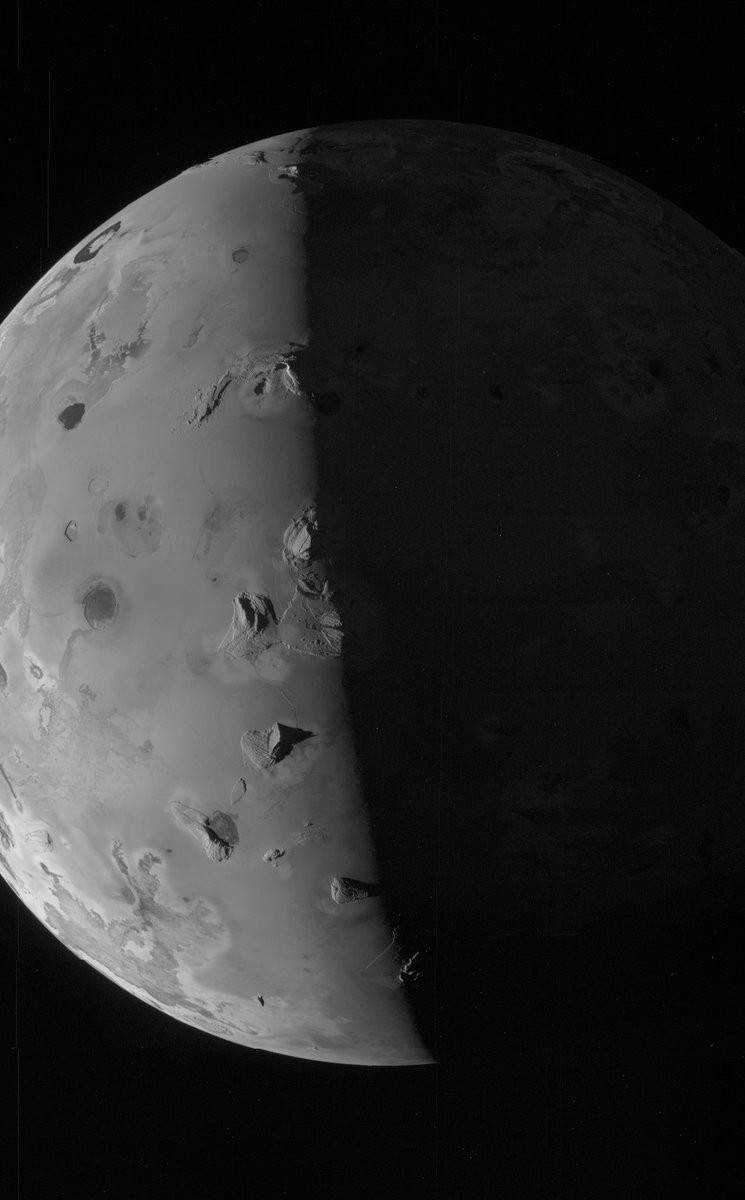

Images from the December 30 flyby were posted by NASA over the New Year holiday weekend, and they provide some of the clearest views yet of this hell-hole world. The new data will help planetary scientists determine how often these volcanoes erupt and how this activity is connected to Jupiter's magnetosphere—Io is bathed in intense radiation from the gas-giant planet.

To date, Juno has mostly observed Io from afar as the spacecraft has made 56 flybys of Jupiter, studying the complex gas giant in far greater detail than ever before. Since arriving in the planetary system in July 2016, Juno has previously gotten to within several thousand miles of the moon. Juno will make another close flyby of Io on February 3, 2024, and this will allow scientists to compare changes on the moon's surface over a short period.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...