Relativity Space is preparing to roll its Terran 1 rocket out to the launch pad in Florida in the next few weeks, setting the stage for its debut flight.

While the rocket is modest in scope, with a capacity to loft about 1 metric ton into low-Earth orbit, the company plans to use this vehicle as a demonstrator for a much larger booster, the Terran R rocket. This ambitious rocket is intended to be a fully reusable vehicle with a payload capacity slightly larger than SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket.

"Almost from the beginning of the company I wanted to build a Falcon 9 competitor, because I really think that’s needed in the market," said Tim Ellis, co-founder and chief executive of Relativity Space, in an interview with Ars.

The impending test flight of Terran 1 may have a lighthearted name—Good Luck, Have Fun—but it has a serious purpose. Relativity needs to show customers that its novel approach to 3D-printed rockets is viable. While ground testing has validated this approach, Ellis knows that the acid test will come with launch, particularly when the vehicle passes through the time period of maximum dynamic pressure, max q.

If the mission successfully demonstrates this, Ellis expects even more customers to sign on for Terran R, which he hopes to begin flying in late 2024. The vehicle is intended to be priced competitively with the Falcon 9 and meet the enormous demand for launch services in the medium-lift market, especially after Russia's war against Ukraine removed the Soyuz vehicle as an option for Western companies.

But first things first.

Terran 1

Relativity recently completed first-stage hot-fire testing of the Terran 1 rocket, and engineers and technicians are now attaching the second stage to the rocket. In a few weeks, the completed vehicle will roll back out to Launch Complex-16 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida for a static fire test and, assuming that goes well, a launch attempt.

"We are confident in our tech readiness to launch this year, and we’re still marching toward that," Ellis said. "But there are a few external factors as we're getting close to the end of the year that could impact the timeline for us. It’s not a guarantee, but it could."

Those external factors include other spaceport users in Florida, including uncertainty around the mid-November launch of NASA's Space Launch System rocket, and blackout periods as part of the military's Holiday Airspace Release Plan. This effectively precludes launches around Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year's Day due to the high volume of airline flights.

Ellis said the company is progressing well toward securing a launch license for "Good Luck Have Fun," and noted that the Federal Aviation Administration accepted its methodology for debris mitigation as well as its trajectory analysis software.

No privately funded company has ever reached orbit on its very first rocket launch, and Ellis is cognizant of that. "While the rocket-loving engineer in me wants to say it's really orbit or nothing for the first flight, I think the business leader part of me knows that customers are going to tell us what enough looks like for the first flight."

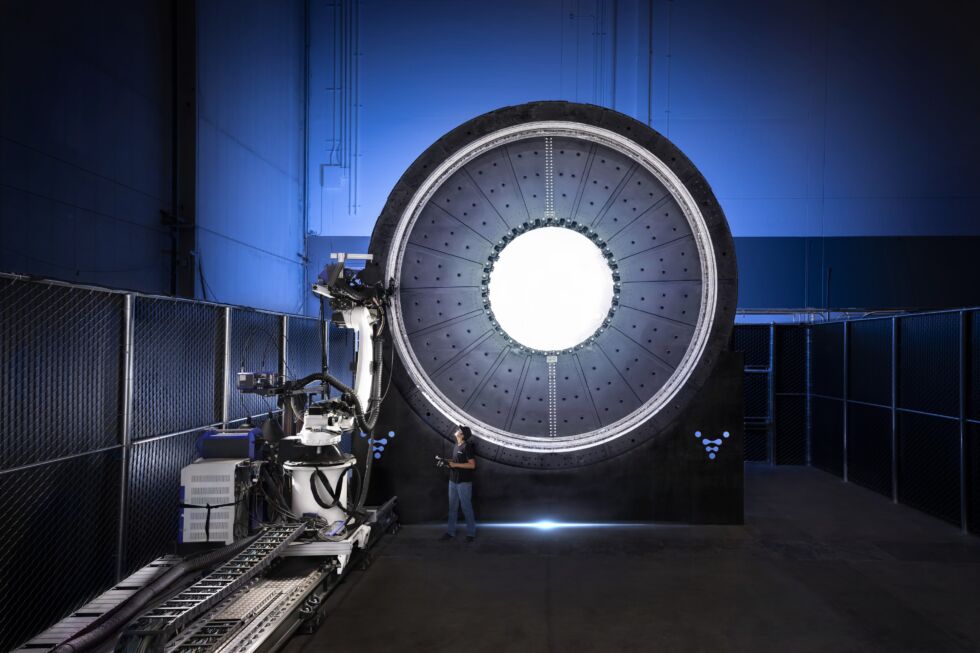

What customers want to see, he said, is a demonstration that a 3D-printed rocket can withstand the rigors of launch. At its core, Relativity is an additive manufacturing company, with the goal of printing the majority of its rockets. By mass, about 85 percent of the Terran 1 is additively manufactured. Can these structures survive max q?

"In many ways Terran 1 is about proving the hypothesis that 3D-printing a rocket is viable," Ellis said. "Doing stage testing on the ground, the structural testing, in my mind, has already really proven the rocket structures that are 3D-printed are strong enough. But I think from a customer perspective, hitting max q becomes an important moment in terms of validating this additive manufacturing model and tech platform. From a visceral perspective on an actual launch, that’s really the moment."

Of course, if Terran 1 does reach orbit on its first attempt, it would be a real breakthrough. In addition to becoming the first private company to reach orbit with a vertically launched rocket on the first try, Terran 1 would be the first methane-fueled rocket to launch and also the first one that was built primarily from 3D-printed parts.

Reader Comments (141)

View commentsLoading comments...